Originally written for Politics of Policymaking Fall 2021 at Columbia SIPA

Policy tool: Randomized controlled trial - health effects of electric induction stoves

Recent research has revealed health problems associated with the use of gas stoves, which emit nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and formaldehyde, all of which can have negative impacts including respiratory issues. (Seals, 2020) An observational study from Australia found that approximately 12% of all cases of childhood asthma are attributable to gas stoves. (Knibbs, 2018)

In response, various organizations have proposed policies to drive the adoption of electric, induction stoves, which produce less pollution. For example, the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) recommends that policymakers “[p]rovide financial incentives, such as tax credits or rebates, that will enable low-income homeowners to eliminate gas stove pollution, including adding plug-in induction stovetops or switching from gas to electric stoves” and that such policies “[p]rioritize homes with children and other at-risk populations.” (Seals, 2020)

While there is compelling evidence that gas stoves pose health risks, no studies to date have assessed health outcomes from replacing gas with modern electric induction stoves.[1] Observational studies such as the Australian study cited above can estimate pollution impacts but cannot account for all lurking or confounding variables.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) could directly study health effects of replacing gas with induction stoves, and provide support for subsidy policies while providing insight for effective targeting of vulnerable populations.

Key considerations in designing an RCT include finding a relevant population and collecting appropriate data.

The RCT population should be selected in line with RMI’s proposal for targeting rebates at vulnerable populations. Therefore, this RCT should study children with asthma living in households with a gas stove.

If cost is no object, administrators could attempt a national study. A more economical option would be a regional study of participants identified through collaboration with New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital, a premier children’s hospital and one conveniently affiliated with Columbia University. Patient selection could follow a protocol similar to that used in Fiks et al., using electronic health records to identify children where asthma is a primary or current health concern. (Fiks, 2015) After working with the hospital and families to find willing participants they would be divided into control and treatment groups.

Data collection would consist of a preliminary survey, followed by health and air quality data collection before and after the health intervention. The preliminary survey would cover indicators related to health, cooking practices (such as frequency of stove use) and building attributes (such as air quality and flow, and kitchen features including exhaust fans).

Following the initial survey, both groups would be observed for a period of time - perhaps six months - before the treatment group would be provided with induction stoves. This initial period would establish a health and air quality baseline. Following the installation of induction stoves for the treatment group, both groups would be followed for another similar length of time. Key information to collect from the ongoing survey would include incidence of asthma attacks and hospital visits, symptom severity, and tests of in-home air quality. Precise study length would be determined by respiratory health experts, although minimally the study must last long enough for families to become comfortable with new cooking equipment and for health effects to be observed.

A viable study must take into account ethical and economic considerations. In working with children, administrators must obtain informed consent from both children and parents, and identify participants without violating privacy. Administrators should also be aware and consider the costs of withholding treatment from the control group. Given the widespread use of gas stoves, however, control group participants will likely not face acute risk.

The primary economic considerations are equipment and study length. Lower-end induction stoves cost around $1,000.[2] For a study with 100 participants, including installation costs, this cost would be non-trivial but not necessarily prohibitive. Study length and staff time needs could be relatively low, as asthma symptoms react relatively quickly to changes in conditions - weeks or months, as opposed to years - and the study could take place in just one region. (Jaakkola, 2019)

Following completion of the study, there are two key policy questions to consider:

-

Are induction stoves associated with changes in health outcomes for vulnerable children, and if so what are they?

-

Are there factors that affect these health impacts, such as housing characteristics, age, or severity of pre-existing conditions?

Both questions are of relevance to policymakers. The first can help gauge whether offering rebates for induction stoves (or other policies to encourage adoption) are an effective tool for protecting public health. The second can help policymakers understand whether certain populations - such as children of certain ages or residents of specific housing types - benefit the most, in order to craft an effective targeted policy.

References

Adane, M. (2021). Biomass-fuelled improved cookstove intervention to prevent household air pollution in Northwest Ethiopia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Environ Health Prev Med, 26(1). 10.1186/s12199-020-00923-z

Fiks, A. (2015). Parent-Reported Outcomes of a Shared Decision-Making Portal in Asthma: A Practice-Based RCT. Pediatrics, 135(4), e965–e973. 10.1542/peds.2014-3167

Jaakkola, J. (2019). Regular exercise improves asthma control in adults: A randomized controlled trial. Nature, 12088. 10.1038/s41598-019-48484-8

Knibbs, L. (2018). Damp housing, gas stoves, and the burden of childhood asthma in Australia. Med J Aust, 208(7), 299-302. 10.5694/mja17.00469

Seals, B. (2020). Health Effects from Gas Stove Pollution. Rocky Mountain Institute. https://rmi.org/insight/gas-stoves-pollution-health/

[1] RCTs have, however, been performed with other types of cooking equipment. (Adane, 2021)

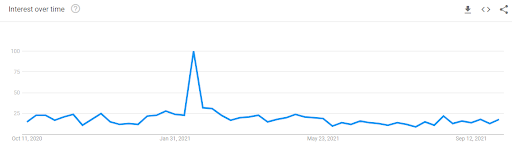

[2] Based on Google Shopping search for “induction stove” on 12 November 2021.